What are differential equations?

Examples of differential equations

The next examples illustrate what some important differential equations look like. Some other matters come up too, for example that solutions to differential equations are functions (not numbers), and that a single equation can have many solutions.

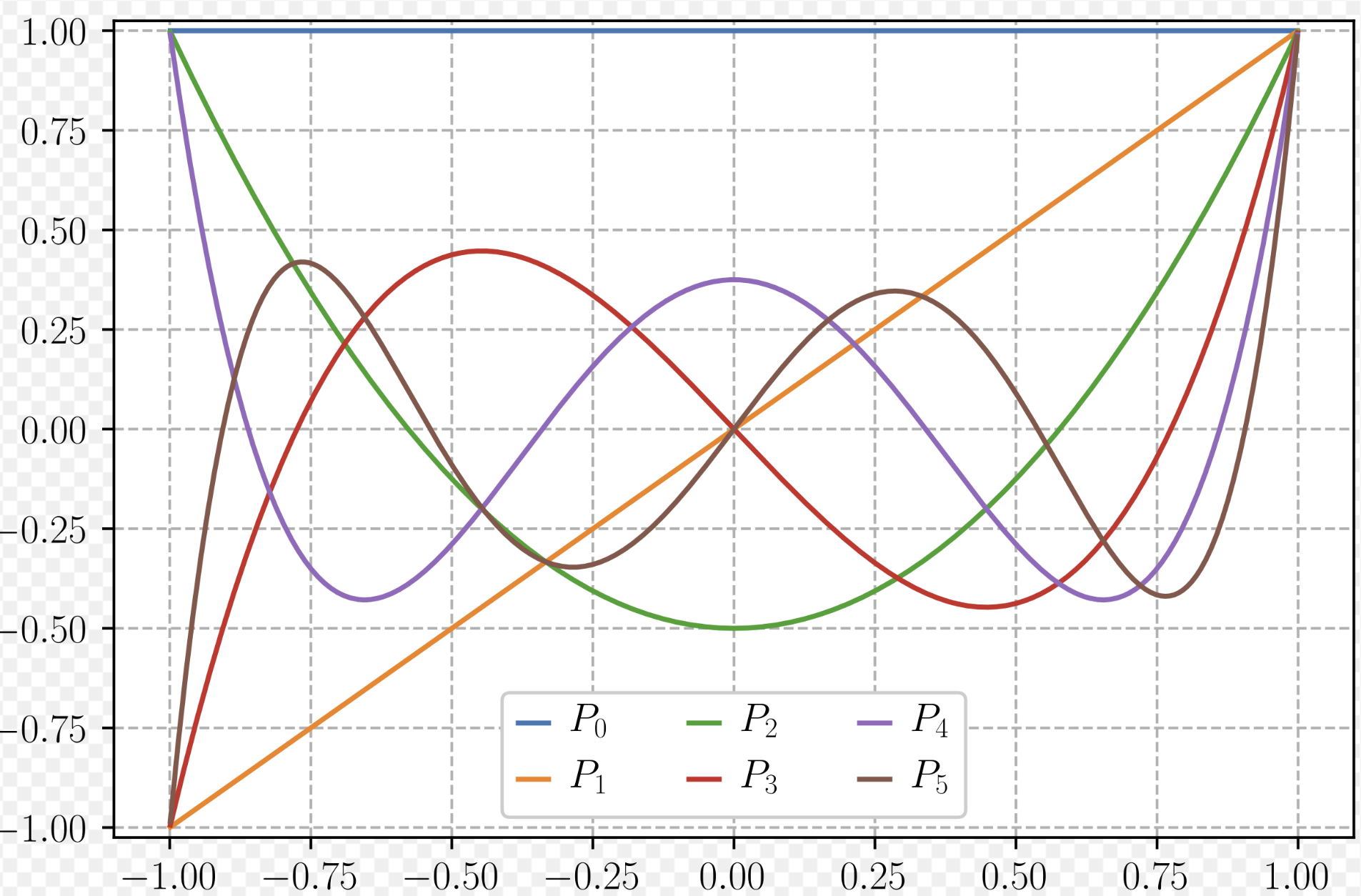

Legendre’s equation:

The solution to this equation is a polynomial

| 0 | 1 |

| 1 | |

| 2 | |

| 3 | |

| These polynomials have many useful properties. Their most important property is “orthogonality”: |

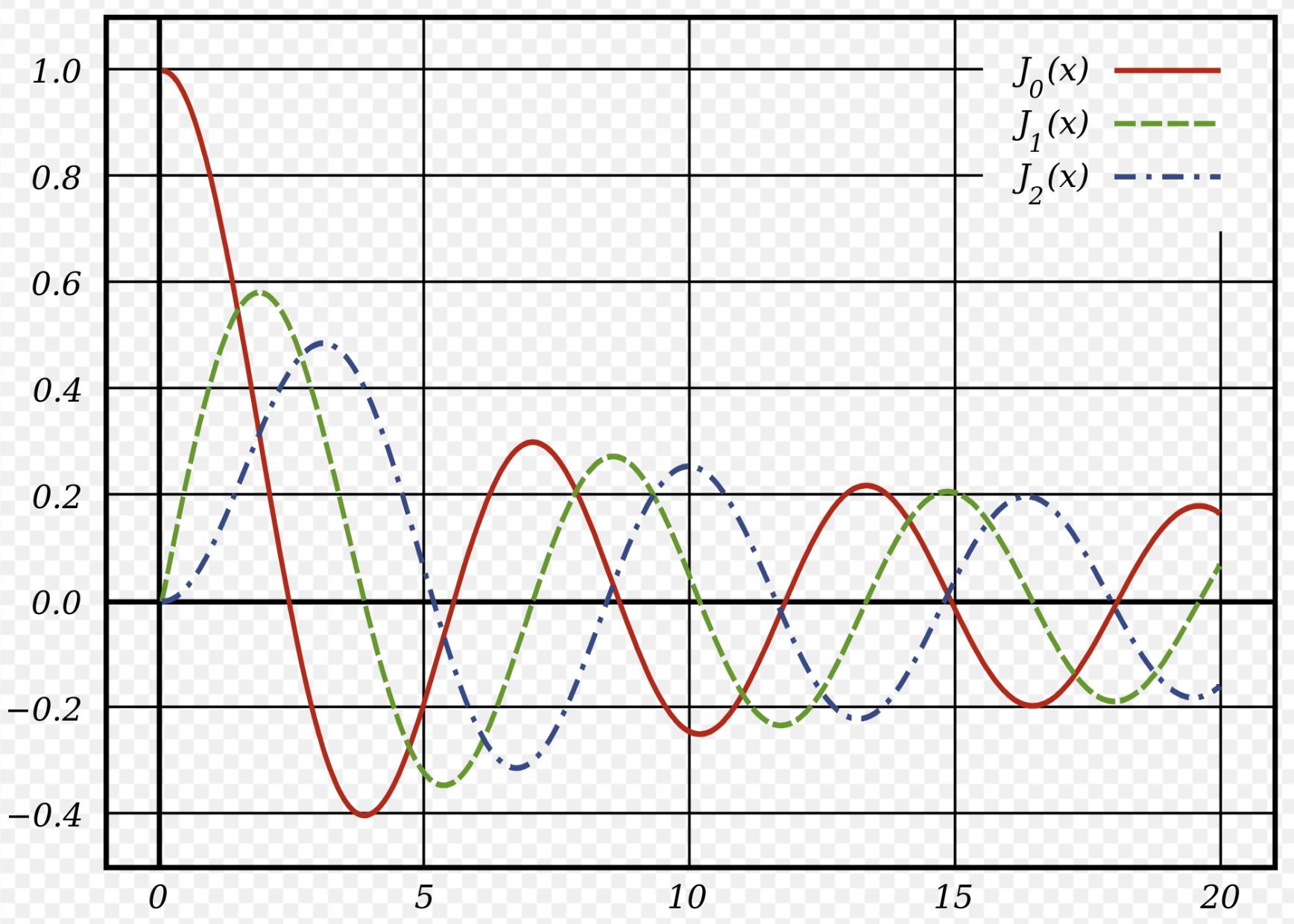

Bessel’s equation:

Solutions to this equation are used to study heat conduction and waves (electromagnetic or quantum wavefunctions).

Airy’s equation:

The solution to Airy’s equation arises in quantum mechanics, optics, and probability.

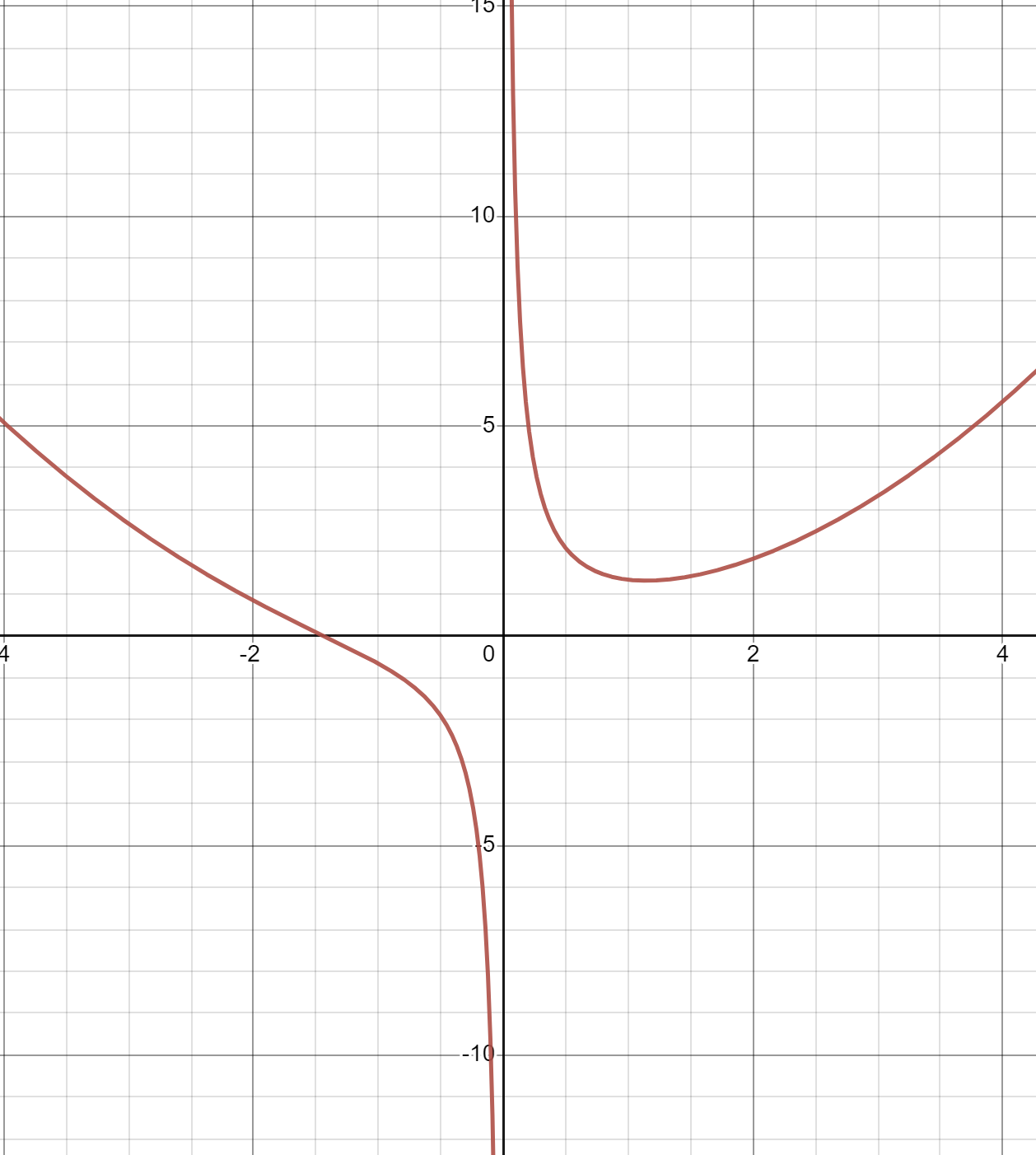

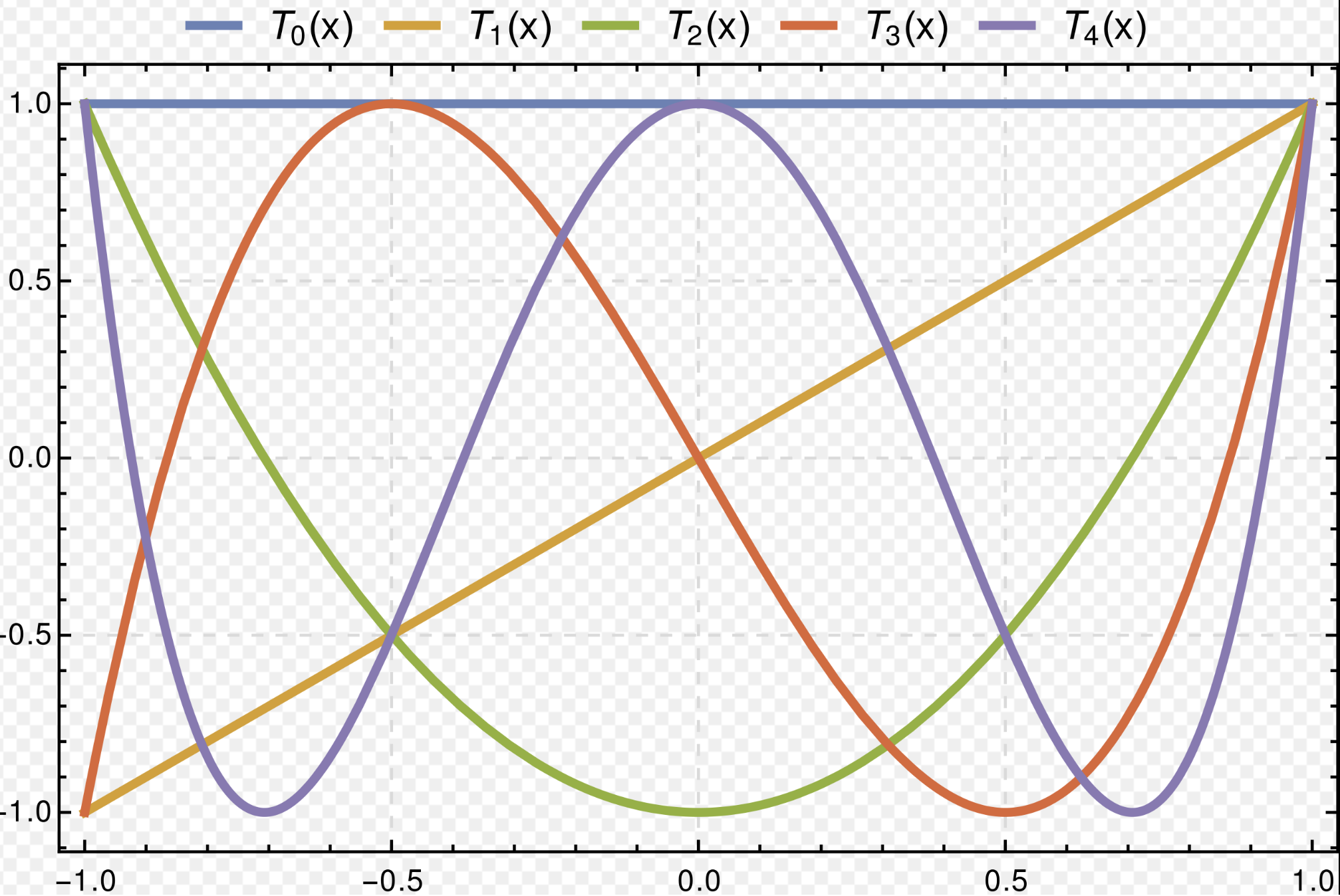

Chebyshev’s equation:

Solutions to this equation give polynomials

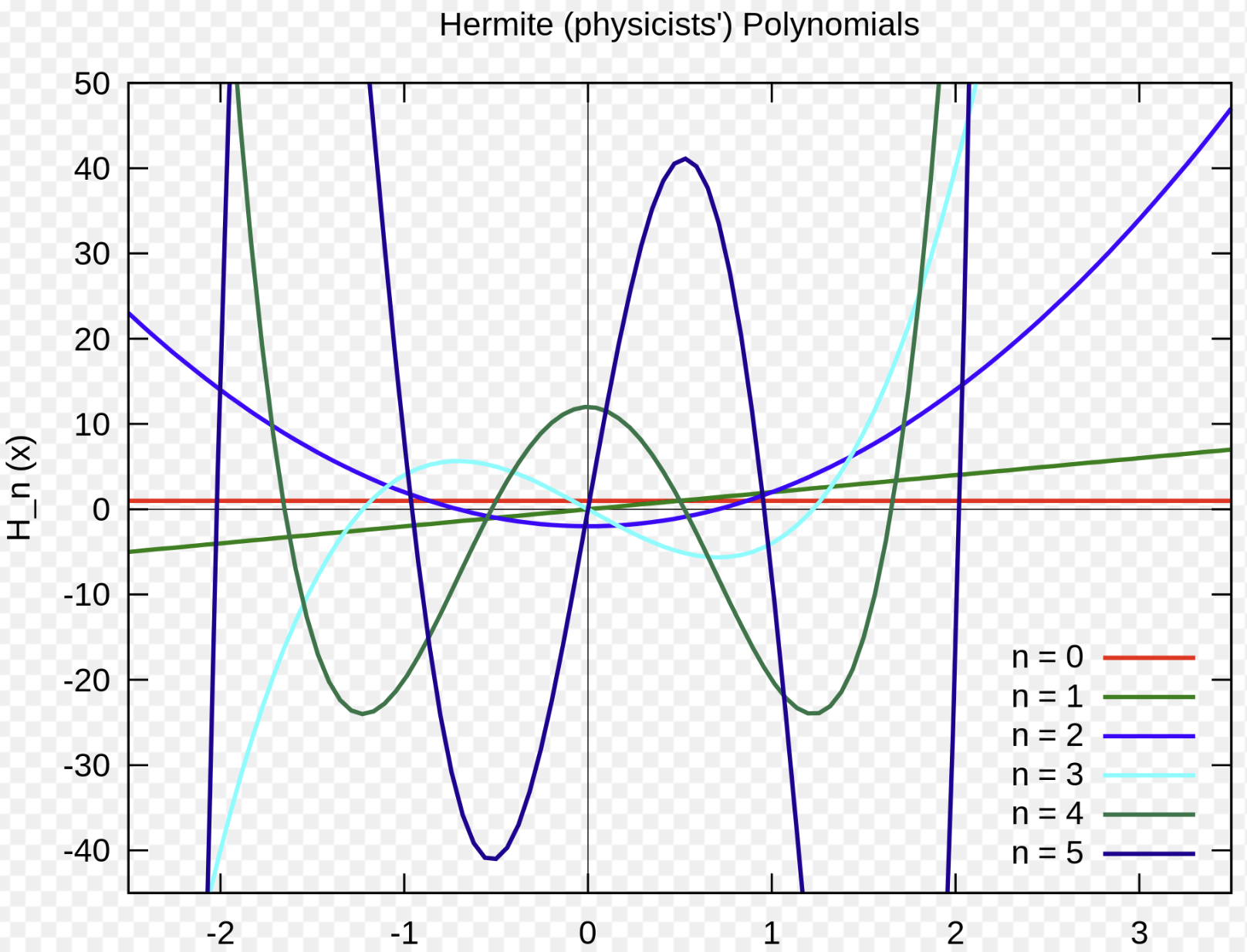

Hermite’s equation:

Solutions to this equation are used in quantum mechanics, signal processing, numerical analysis, and probability.

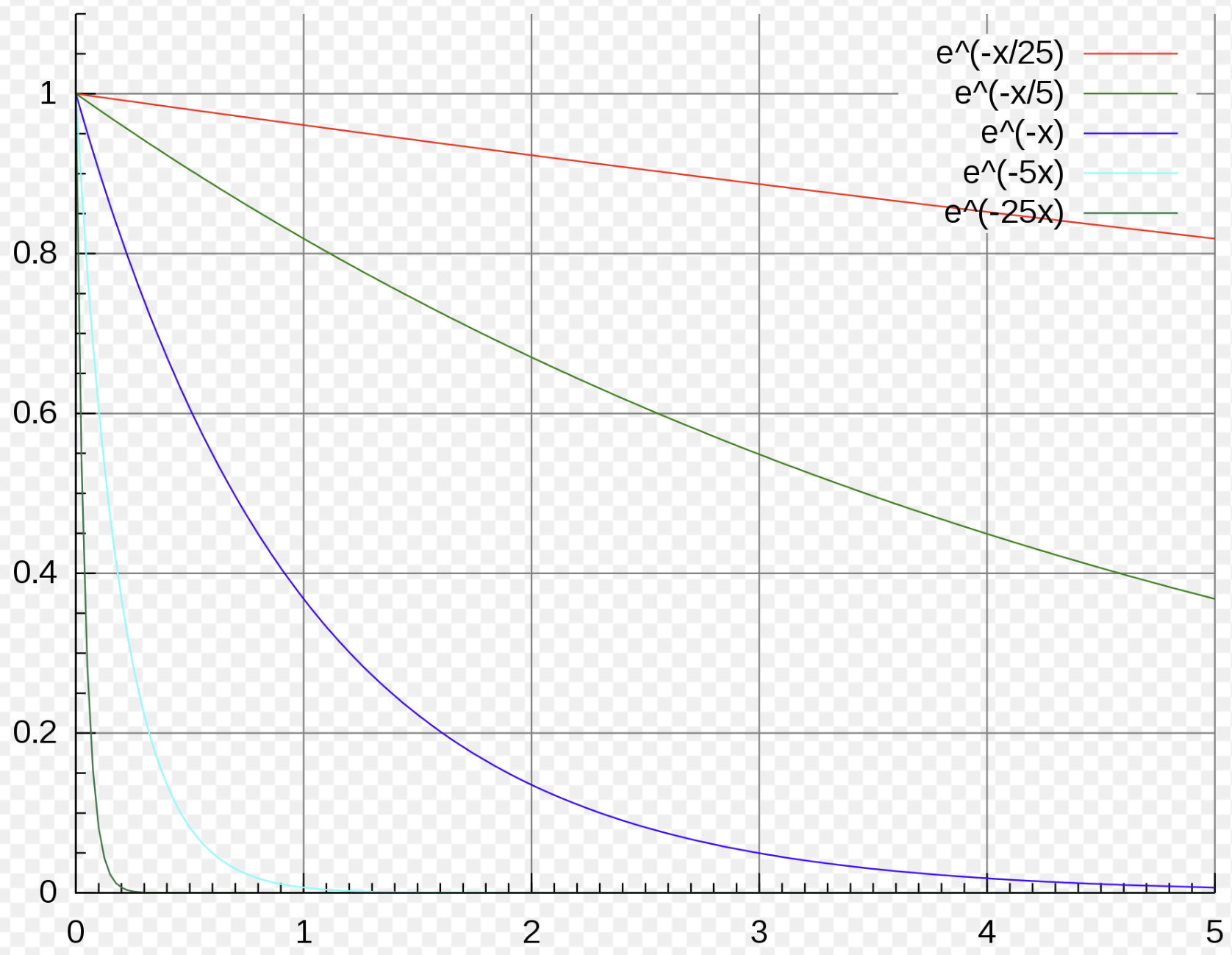

Exponential decay:

This equation models countless physical processes.

Concepts of differential equations

What we typically mean by a “differential equation” is a function

for all

A differential equation is called explicit when it can be written with the highest derivative isolated, on the other side:

Sometimes a differential equation is “solved” by finding an equation relating

Ordinary differential equations involve only ordinary derivatives, while partial differential equations involve partial derivatives.

Usually we assume that

There is a fundamental distinction between linear and nonlinear differential equations. A linear differential operator is a linear function taking functions to functions. For example:

Question 02-01

Linear operator

Show that the example differential operator above satisfies the linearity equation for two given functions

and . Let ; show that:

Linear differential equations are defined as those corresponding to a linear differential operator. (By applying the operator to

First-order equations

A first-order (explicit) ODE looks like this:

for some function

Many techniques for solving first-order ODEs come from reverse-engineering results of calculus. In this respect, solving ODEs analytically is like taking integrals (finding antiderivatives) analytically. In fact, antidifferentiation is itself one of the techniques: when

Direct integration

A differential equation of the form:

has a set of solutions given by

This kind of differential equation is really a part of basic calculus. A few things to emphasize en route to more complicated ODEs:

- There is a family of solutions parametrized by some constant

. (This will become a pattern.) - This family is a complete set: there are no other solutions. (Why not?)

- A particular solution is determined (selected from this family) by a choice of initial condition, which consists of a point

that should lie on the solution. - Consider that the derivative value specifies the direction of travel. So the initial condition is a starting point, and

gives the data of which way to go, changing course along the route.

This technique can be applied in a series for simple ODEs of higher order. For example, the ODE

is solved by taking two antiderivatives. Let

To specify a particular solution, one provides two points

Question 02-03

Checking things

- For the first-order equation above, why must

give a complete set of solutions? - For the second-order equation, explain how to obtain the formula

.

Higher order

(Big Bonus question. Not for the faint of heart!)

- Can any two points

and be chosen? - Now iterate the process: consider

and solve using multiple consecutive integrations. Describe the family of solutions. What constraints are there on the set of points needed to specify a particular solution?

Instead of providing multiple points lying on the solution, one can choose a single value

Separable equations: substitution

Consider again the general form of an explicit first-order ODE:

This ODE is called separable when

Consider any function

Now let

is equivalent to the equation

so we end up with

which is solved by integrating both sides in

where

Think about this equation

Many authors describe the solution method a little differently. Starting with

write it as

and “integrate” both sides, summing up the differentials:

This yields

as before.

This method is easy to remember, and is acceptable to use on an exam or HW, but it is not really standard calculus procedure, since it relies on ambiguous rules about differentials. (Normally in calculus books differentials are considered purely mnemonic devices.)

Example

Separable ODE

Problem: Solve the equation

. Solution: The given equation can be written Integrating both sides, obtain

Applying

on both sides: Applying the exponent sum rule and writing

, we get Here

because for any . However, we can allow by removing the absolute values. So that family of functions is the same as this family: Note that the

solution, , is valid but isn’t generated by separation of variables because of the division by that was performed in the first step.

Exercise 02A-01

Tricky signs

Check and explain all absolute values and signs (including

) in the previous example.

Example

Integral curves

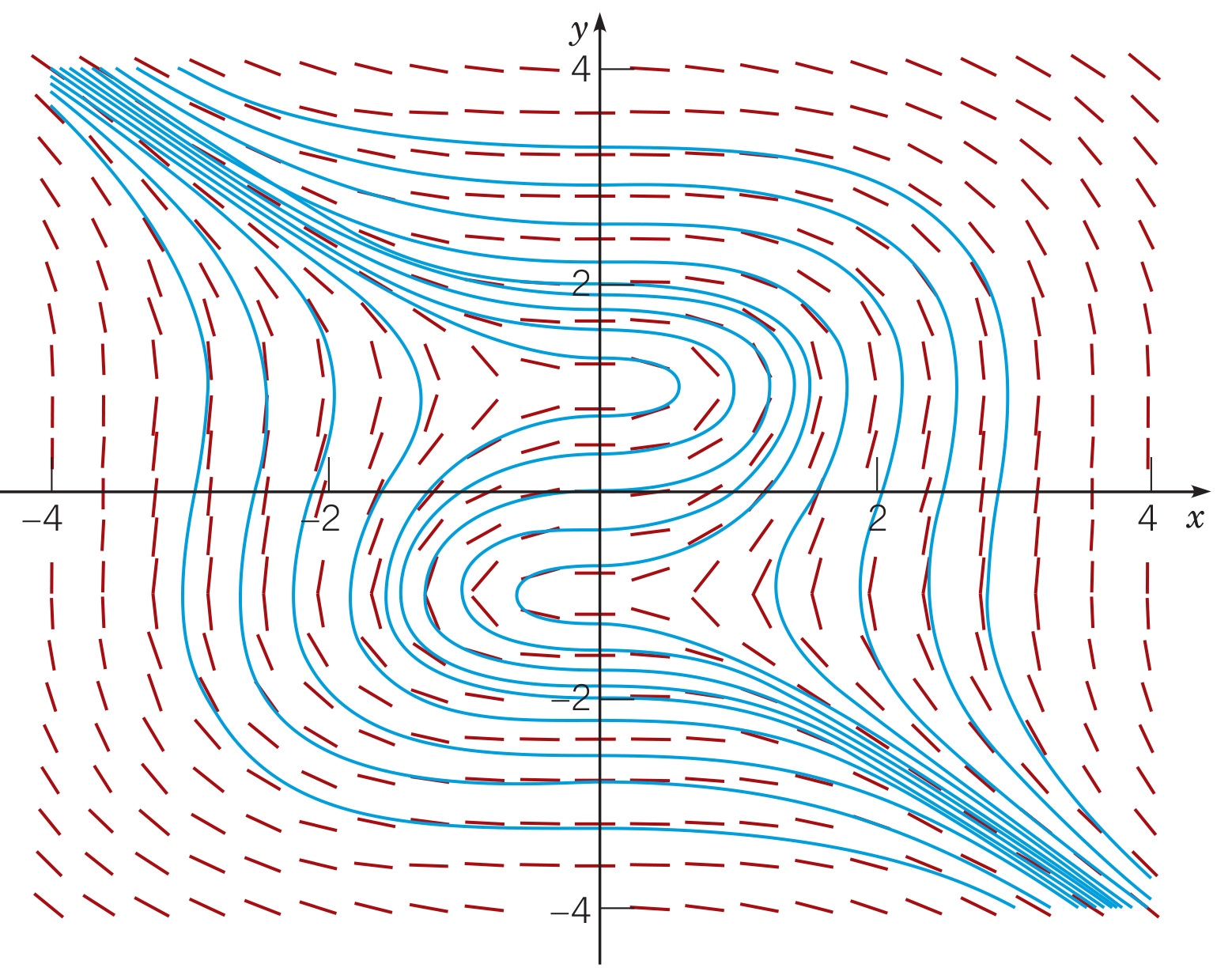

Problem: Solve the separable ODE:

Solution: Rewrite this as:

and integrate both sides to obtain:

This equation specifies a family of integral curves. For the integral curves, we do not need to solve for

in terms of . Here is a depiction:

Exercise 02A-02

Separable equations: basics

Solve the equations:

- (a)

- (b)

Exercise 02A-03

Separable equations: tricky trig

Solve the equation:

After finding the basic solution, check over the signs and absolute values of everything.

Exercise 02A-04

Particular solution

Find the particular solution to

which includes the point

.

Linear equations: product rule

First-order linear equations have this general form:

These equations are solved using the product rule together with an “integrating factor”

Now, multiply the original equation on both sides by

Integrate both sides with respect to

which can be solved for

Example

First-order linear

Problem: Solve the equation:

Solution: First divide by

to recover the standard format: Now the integrating factor we need is

. Multiply everything by this factor: If

everywhere, we can drop the absolute value signs obtaining . If everywhere, we would need to introduce minus signs (recall that and when ), obtaining ; but this we can multiply by and obtain the same equation, namely: Let us solve this and come back later to consider the possibility of

changing signs. The sum on the left is the output of the product rule:

. Now integrate in to find a family of solutions: This family, for various values of

, is our proposed solution to the ODE. Now reconsider the absolute values. Suppose

. If we take a solution curve with , then the entire curve will satisfy because as . Similarly, if we start with , then as . No solution crosses over . Now if we can say the same thing but with and , respectively, instead. Therefore our analysis using cases and is justified.

Exercise 02B-01

Linear equations: basics

Solve the following ODEs, giving a complete family of solutions:

- (a)

, - (b)

.

Exercise 02B-02

Linear equation: particular solution

Find a particular solution of the following ODE which passes through the point

:

Exact equations: gradients

A final technique is based on more advanced calculus.

Recall the theorem of vector calculus:

Curl-free fields are gradients

Suppose

is a vector field on with zero curl: . (Assume the region is simply-connected.) Then there is a scalar field whose gradient recovers the vector field: .

Writing out the components, this theorem says that if

then there is a function

Now, finally, let

Let

Writing

Here is a summary of our reasoning:

Exact equations

Suppose the differential equation written either in form (A):

or in form (B):

satisfies

. Then it has a family of solutions given by the level curves , where is a function satisfying and .

Algebraic summary

A more algebraic formulation of the same theory goes like this:

If

, then it is possible to find such that and . In this case the equation can be written

using the chain rule, and this has as solutions the family of integral curves defined implicitly with constants

:

Example

Solving an exact equation

Problem: Solve the ODE:

Solution: First we check that

: Now we seek

with and . First integrate in : where the “constant” can be any function of

. Now , so and . Therefore our solution family of integral curves is given by: for

.

Exercise 02B-03

Checking exactness

Which of the following ODEs are exact?

- (a)

- (b)

- (c)

- (d)

Exercise 02B-04

Solving an exact equation

Show that the ODE is exact, and solve it:

Problems: due Monday 29 Jan 2024 by 1:00pm

Problem 02-01

Decide whether the ODE is separable, first-order linear, or exact, and then solve it:

- (a)

- (b)

- (c)

- (d)

- (e)

- (f)

Problem 02-02

Exact equation: 2D gradient emanating from charged particle

Consider an electric field

in given by: Find a scalar function

whose gradient is . What are the level curves of ? Now write an exact differential equation whose integral curves are these level curves of .