Transformation and reduction

So far we have seen how to solve differential equations by direct integration, by separation of variables, by integrating factors: conversion to a product (linear equations), and by gradients (exact equations).

Many differential equations do not immediately appear to have the standard form to which these methods are applicable, but in fact these methods can be applied after performing a transformation. The possibility of some of these transformations can be checked systematically, but for others we rely on an art – not a mechanical science – of finding an appropriate substitution. This art is based on experience and honed by practice.

Homogeneous equations: conversion to separable

Homogeneous functions

A function is homogeneous when the input variable appears everywhere in the same degree. More precisely and technically,

In other words, a function is homogeneous when the action of scaling the inputs simultaneously can be factored out to an action of scaling the output.

For example, these functions are homogeneous:

whereas these are not:

Homogeneous differential equations Now, suppose we have a differential equation in the form:

where

Homogeneous substitution

Suppose

and are homogeneous of the same degree . Then depends only on the ratio :

Separability then occurs because:

so the equation

and the general solution is the family of curves given by:

Alternate format The differential equation

is homogeneous if

Question 03-01

Homogeneous?

Is

a homogeneous differential equation?

Example

Homogeneous equation

Consider the differential equation

. Assuming , this is equivalent to the homogeneous equation . Define , and we find: The solution is therefore

, or for any , i.e. .

Example

See an example in “Families of integral curves” below, where we solve the homogeneous equation

Exercise 03A-01

Homogeneous equations

For the following differential equations, show that they are homogeneous, and then solve them by substitution and separation:

- (a)

- (b)

- (c)

Linear quotients: almost homogeneous Suppose we are given a differential equation

This equation is not homogeneous, but it is easily converted to a homogeneous equation by a change of variables. Find

Then by plugging in

The left side transforms as desired:

Question 03-02

Transform linear quotient to homogeneous

Transform this equation to a homogeneous equation:

Integrating factors: conversion to exact

Sometimes an equation

is not exact, but there is a function

Question 03-03

Integrating factor

Check that

is an integrating factor for .

How can we find such a function

Integrating factors: single variable

- Check

: if the function depends on alone, we can use . - Check

: if the function depends on alone, we can use .

Exercise 03A-02

Method of integrating factors

Show that if the function

depends on alone, we can use as an integrating factor and the resulting differential equation becomes exact.

Example

Integrating factor: converting to exact

Consider the differential equation

. This is not exact because while . However, is a function of alone. Therefore we can use as an integrating factor. Multiplying through by produces the equation , which is exact because now .

Exercise 03A-03

Integrating factor: converting to exact

Convert the following to exact equations by finding and applying integrating factors.

- (a)

- (b)

Reduction of order

Some second-order ODEs can be reduced to first-order ODEs by substituting

If the equation is missing

If the equation is missing

We therefore try to solve the equation

Question 03-04

Reduction of order

Reduce the order of the following two differential equations. (No need to solve them.)

- (a)

- (b)

Example

Reduction of order

Consider

. This equation is missing so we can reduce it to a first-order equation by letting and . The equation becomes which is separable. The solution is , and this implies . (Integrating to obtain .) Consider

. This equation is missing so we can reduce it to a first-order equation by letting and . The equation becomes which is separable. The solution is . This is a new differential equation which is also separable. Its general solution is .

Ad hoc transformations

Bernoulli equations

The Bernoulli equations look like linear equations but with an extra factor of

If we substitute

Exercise 03A-04

Bernoulli substitution

Show that substituting

does indeed convert the Bernoulli equation to a linear equation.

Exercise 03A-05

Solving Bernoulli equations

Solve the Bernoulli equation

.

Linear substitutions

If in the general form of an explicit first-order equation

then the equation

Swapping roles

It is sometimes effective to transform an equation to a known form by swapping the roles of

Inverse functions derivatives

If

, then so . Now treating , we have . Therefore .

Example

Swapping roles

Consider the differential equation

. If we change to , the equation becomes or

or . (This is linear of the form .) To solve it we write and thus or .

Exercise 03A-06

Swapping roles

Reverse the roles of

and to solve: .

Families of integral curves

Each first-order differential equation leads to a family of curves, its integral curves (solution curves).

Conversely, each family of curves given by a single equation with a single parameter leads to a differential equation, and it is the equation whose solution curves are given by this family.

This correspondence

works in general, assuming the family of curves is provided by an equation (without derivatives) with a single varying parameter.

Example

Family of curves

For example, start with the family given by

. Differentiate both sides:

. Now plug in from the original equation, and we get the differential equation: Conversely, let us solve this differential equation. Write it as:

This is a homogeneous equation, so we can substitute

: Integrating both sides, applying

, and substituting gives: Now multiply the fraction by

and cross multiply to obtain , which is equivalent to assuming . Allowing , we have the original equation.

Something interesting we can do is define the orthogonal family of curves to a given family of curves. The orthogonal family is the family such that each curve is perpendicular to every curve of the original family.

For example, if one family of curves represents electric field lines, its orthogonal family represents equipotential lines. Or, if one family represents the level curves of a function, its orthogonal family represents the lines of steepest ascent.

The orthogonal family can be found from the original family by first computing the differential equation

Example

Circles and rays

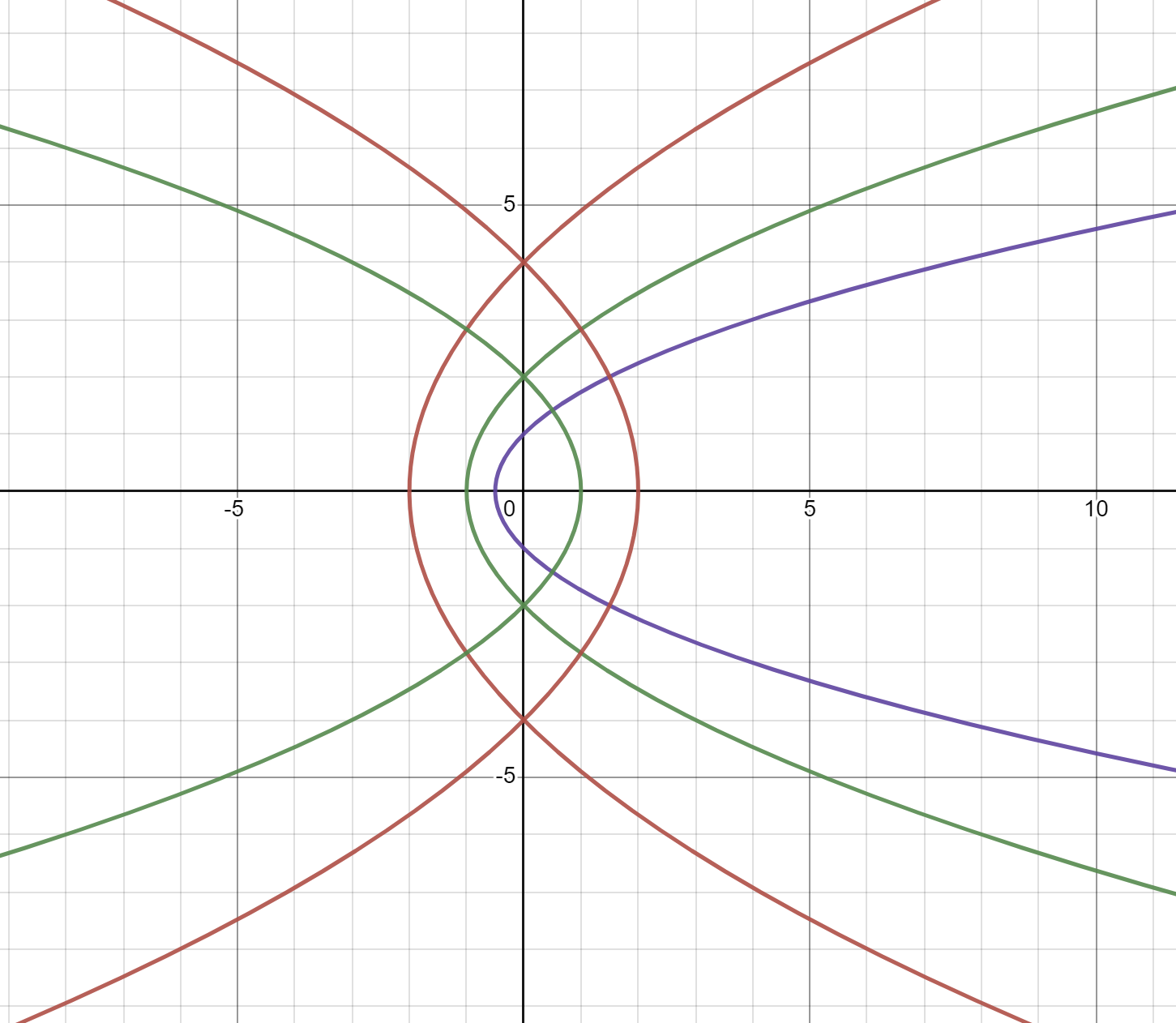

We verify that the family of rays emanating from the origin is the orthogonal family to the family of circles centered at the origin. The family of circles is given by

. This corresponds to the differential equation . The orthogonal family is then given by . Separating variables: so and thus for . This is the family of rays.

Exercises B

Exercise 03B-01

Homogeneous

Solve the following homogeneous equations by substitution of

. You should first write the equation using a single quotient and then divide above and below by .

- (a)

- (b)

Exercise 03B-02

Integrating factors, conversion to exact

Solve the following differential equations by finding an integrating factor

or .

- (a)

- (b)

Exercise 03B-03

Bernoulli

Solve the following Bernoulli equation:

.

Exercise 03B-04

A self-orthogonal family

Show that this family of curves is orthogonal to itself:

. (Hint: divide the curves into two families, one with and the other with .) Here’s a picture showing the curves for (opening rightward) and (opening leftward).

Problems due Monday 5 Feb 2024 by 1:00pm

Problem 03-01

Homogeneous; linear quotients

- (a) Solve the homogeneous equation

. - (b) Solve

using linear quotients.

Problem 03-02

Reduction

The differential equation

is missing both and . It can therefore be solved by reduction in ways. Solve it using both methods, and check that your solutions are equivalent to each other.

Problem 03-03

Swapping roles

Reverse the roles of independent and dependent variables

and to solve:

- (a)

- (b)

Problem 03-04

Integral curves of homogeneous equation

Consider the integral curves of a homogeneous equation. Take a straight line through the origin. Show that this line crosses all the integral curves at the same angle of intersection.

Problem 03-05

First-order families

The family of curves solving a first-order linear differential equation has the general form

. Now suppose we start with a family of curves in this form. Find the differential equation corresponding to this family and show that it is first-order linear.