Fundamental Theorem of Line Integrals

The following conditions for a vector field

is path independent, in the region (which is simply connected, i.e. no holes), for some scalar field .

When these conditions hold,

(Note: when the domain is not simply connected, then the curl condition is not strong enough, but the first and last conditions are still equivalent to each other and the word ‘conservative’ applies when these two conditions hold.)

The Fundamental Theorem of Line Integrals gives the value that is common to these line integrals over various paths:

FT of Line Integrals

For

any path from point to point , we have:

If

Derivation of FT of Line Integrals

Take any parametrization

of given for . Now . By the chain rule for paths (in reverse), this is equal to . So can apply the ordinary FTC:

Exercise 14A-01

FT of Line Integrals: elevation gain

Consider the vector field

. Choose any path between and . Verify the FT for line integrals by computing the elevation gain on your chosen path in two ways (computing both sides of the FT). For the right side, you will need to first find a field such that .

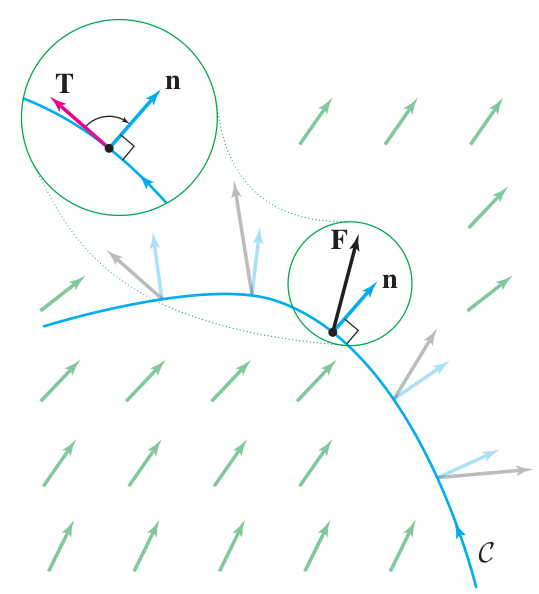

Line integrals III: vector fields, across

The across vector line integral is the integral of a vector field over a curve according to its alignment with the normal vector to the curve. It measures how much the vector field flows across the curve. It does not depend on the chosen parametrization (i.e. on the speed), but its sign depends on the direction traveled along the curve. It is given for a parametric curve

Here

The integrand

The quantity computed by this line integral is sometimes called the flux across the curve.

This line integral is defined for curves in the plane, since the normal vector

Example

Vector line integral: flux across a path

Problem: Suppose

. Compute the flux of across the curve for (oriented left to right). Solution: Use for . Then and . At , has the value . So , and .

Exercise 14A-02

Vector line integral: flux across a path

Let

, and the line segment from to . Compute the flux of across .

Divergence

Divergence as a derivative operator

Start with a vector field

From this

One can remember this formula using the “vector”

This formula naturally extends to higher dimensions. For example, in 3D we have:

Example

Divergence of vector fields

Consider the vector field

. This is a radial field where each vector has length . everywhere. Now consider the vector field

. We have except at , where it is infinity (undefined).

In physics it is common to use polar (or cylindrical or spherical) coordinates because many problems have rotational symmetry. The derivative operators of vector calculus can be expressed in these coordinate systems.

Example

Divergence in polar coordinates

Let

give a vector field in polar coordinates. Here and are scalar coordinate functions, is the unit vector in the radial direction, and is the unit vector in the direction. Problem: Find a formula for the divergence in polar coordinates. Solution: Write

in terms of polar coordinates. We have in Cartesian coordinates: so:

The chain rule gives us formulas to convert derivatives:

So we obtain, after some cancellation and rearranging:

Polar divergence looks different

Given a vector field with polar coordinates

and , its divergence is given by:

Exercise 14A-03

Polar divergence

Suppose

are the Cartesian components for with some integer. Write this vector field using polar coordinates, and compute using the polar formula for divergence. Repeat the exercise with .

Divergence as measure of expansion

The divergence can be explained as a measure of expansion of the vector field at each point in space. (Negative divergence means contraction.) If the vector field corresponds to the velocity of a fluid flow, then divergence measures the rate at which fluid flows out of (or into) each point. We can verify this interpretation by using a vector line integral to measure the flow out of a circular loop, and then shrink the loop down to an infinitesimal loop.

Suppose

Calculate this integral using linear approximations for

We have:

, where the partial derivatives are evaluated at .

Now

In the limit as

Divergence Theorem

The calculation showing that divergence measures flow out of a loop can be done for a box-shaped loop instead of a circle. When two boxes are glued side-by-side, flow out of one box and into the other contributes positively to the line integral around the first box, and negatively to the line integral around the second box, so these contributions cancel in the sum. By subdividing a region into infinitesimal boxes, writing

Divergence Theorem

When

is a region of the -plane enclosed by its boundary curve , then:

The way to think about this theorem is that

When

Green’s theorem revisited

In 2D, it turns out that the divergence theorem and Green’s Theorem are actually restatements of the same fact about pairs of scalar functions.

Suppose

Now rotate the vector field clockwise by

Furthermore,

Putting this together, the two sides of the divergence theorem become:

So, in 2D, Green’s Theorem and the divergence theorem express the same relationship about the functions

Problems

Problem 14-01

Faster calculation of line integral using divergence

Let

be the box in the -plane defined by and . Let . Compute the line integral in two ways:

- (a) using separate line integrals over the four sides of the box,

- (b) using a double integral over the interior of the box.

Problem 14-02

Heat equation

Suppose the temperature in a region is given by the scalar field

. Heat flows from hot to cold, following the negative temperature gradient . The rate of total heat flow into a microscopic disk

enclosed by the circle (radius , centered at ) is the vector integral of heat flow across the loop , namely: . Furthermore, the rate of change of is proportional to the net heat flow into (assuming is small enough). Suppose that all temperatures are static in a region

. (This doesn’t mean all temperatures are equal, since there could be a source or sink of heat on the boundary and a temperature gradient across .) This implies that the net heat flowing into and out of any disk fully contained within is zero. Using the divergence theorem, explain why the temperature across

must satisfy the partial differential equation . (Recall that the Laplacian operator applied to gives .)

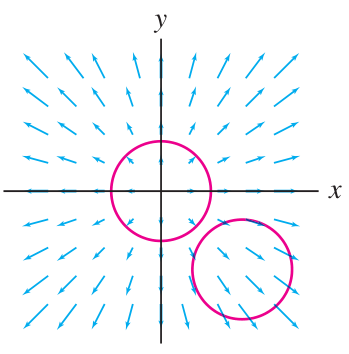

Problem 14-03

Electric field: loop detector of contained charge

The planar electric field

generated by a point charge at the point has the form: Find the total electric flux exiting any given loop

in the plane. Your answer should be one value for any loop that encloses the point , and another value for loops that do not. For any loop that does not enclose

, consider the value of in the region of the loop and apply the divergence theorem. You cannot apply the divergence theorem to a region containing the point

because is not defined at . So, for a loop that does enclose , you should first compute the answer directly for a small circular loop inside the given loop, and then apply the divergence theorem to the region enclosed between the larger given loop and your small circular loop.